Kozhikode mourns yet another victim of the rare but deadly amoebic meningoencephalitis, commonly known as Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) or “brain-eating amoeba” infection. On January 5, 2026, Sachidanandan (72), a resident of Puthiyangadi in Kozhikode, passed away at a private hospital after battling the infection for a week. This marks the first reported death from PAM in Kerala this year, raising fresh alarms in a state that saw 170 cases and 42 fatalities in 2025 alone.

A Sudden and Silent Killer Strikes Again

Sachidanandan’s ordeal began with severe vomiting, a common early symptom of PAM that often mimics other ailments. Hospitalized promptly, tests confirmed the presence of Naegleria fowleri, the free-living amoeba responsible for this devastating brain infection. Despite medical intervention, his condition worsened rapidly, leading to his demise on Monday. Relatives noted that he had no recent history of swimming or exposure to known contaminated sources, highlighting the stealthy nature of this pathogen. Health authorities have launched an investigation, collecting water samples from the well at his Puthiyangadi residence for testing. No source has been traced yet, but officials emphasize vigilance, especially during Kerala’s warm months when stagnant water bodies become breeding grounds for the amoeba. Sachidanandan is survived by his wife Geetha and children Nirmal Raj, Remya, and Vinaya, who now grapple with profound grief amid community condolences.

Understanding PAM: The Brain-Eating Threat in Kerala

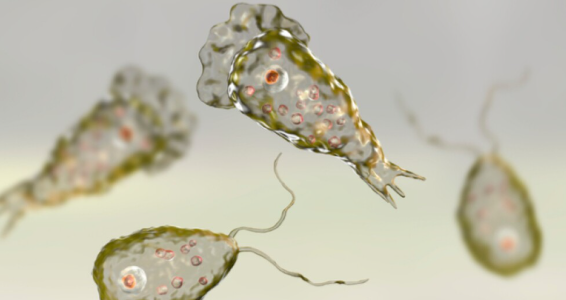

PAM is caused by Naegleria fowleri, an amoeba thriving in warm freshwater like ponds, lakes, rivers, hot springs, and poorly chlorinated pools. It enters the body through the nose during water activities, travels to the brain, and destroys tissue, leading to meningoencephalitis. Symptoms fever, headache, vomiting, stiff neck, seizures, and confusion appear 1-9 days post-exposure and progress fatal within days, with a 97% mortality rate worldwide. Kerala has been an epicenter, reporting 211 cases and 53 deaths since 2023, with 2025’s surge attributed to better detection rather than an outbreak. Kozhikode alone saw multiple cases last year, including alerts after three infections and a death in mid-2025. Unlike clustered outbreaks elsewhere, Kerala’s cases are often isolated, linked to everyday exposures like bathing in contaminated wells or stagnant water.

Government Response and Community Vigilance

The Kerala Health Department, under guidelines from ICMR and WHO, has ramped up measures: district microbiology labs for rapid testing, healthcare worker training, school awareness programs, and water quality surveillance. In Kozhikode, advisories urge avoiding untreated water for nasal irrigation or bathing. Last year’s data presented in Parliament underscores the crisis, prompting calls for stricter pond cleaning and chlorination. While not an epidemic, experts stress early diagnosis boosts slim survival odds via drugs like Amphotericin B. The state closed risky sites like the Akkulam swimming pool after a case, proving proactive steps work.